Gentlemen,

I know there are a thousand critics out there, and I think I personally may have 995 of them, but I did want to take a moment to express my disappointment with your May 3rd piece on horse slaughter. I think you fell for the false framing of the issue by proponents of slaughter, and you validated the anecdotes of a handful of people and turned them into a fact pattern. I don’t think it was reporting at its best.

There were some actual errors, including the mention that the Congress took the action of specifically “authorizing funding for inspections” at horse slaughter plants. The Congress did no such thing. It simply chose not to include language that specifically barred funding for inspections. In fact, every time the full Senate or House has voted on the issue, the outcome has been lopsided in opposition to horse slaughter. In this case, a couple of conferees to the Agriculture spending bill dropped the House-approved language barring funding. You’ll find no language in the appropriations bill that mentions that horses should be slaughter, and there’s definitely no authorizing language to that effect.

But that’s not my main gripe. My main concern is the false framing of the issue. The Humane Society of the United States operates the two largest horse sanctuaries in the United States – one in Texas and one in Oregon – and we also have an Animal Rescue Team and veterinary teams that roam the country to come to the aid of animals and communities in need. There’s certainly an unwanted horse problem in America, but there’s barely a shred of evidence that people are turning horses loose left and right in this country, as your news story suggested. Certainly, there’s an unwanted horse problem, but that’s been the case forever. Similarly, there’s always been a crowd that’s wanted to make a few dollars in selling horses to slaughter, rather than to provide lifetime care to their animals or to provide the animals with a decent death. That’s selfishness and greed at work, and as with so many people who exploit animals, they don’t want to admit it. They try to attach some high-minded rationalization to their behavior, trying to cast themselves as protectors of the animals. Every horse slaughter advocate thinks they’re an animal lover, just as every factory farmer, every dogfighter and every cockfighter does, too.

The core argument of the horse slaughter crowd — the animal advocates, led by HSUS, shut down the slaughter industry and now people are turning the horses loose because they have no place to send them — suffers from a logical fallacy. As you know from your research, about 130,000 U.S. horses went to slaughter last year – about the same number that went to slaughter each year, in the years when the three U.S. plants were operating. The killer buyers and auctions are operating in precisely the same settings in the U.S. as they were before, but they just then ship the horses to our North American neighbors. If we have the same number of horses going to slaughter, and the same auction points in our country, and the same foreign markets, then how are the economic incentives and same underlying mechanics any different now than prior to 2007?

Again, there’s no quarrel from me that you included the arguments of the proponents of slaughter. And to your credit, you did include some voices against slaughter. But it was lopsided, and there was little substance in the arguments from critics – just opprobrium. I was dumbfounded when I read the piece, but I’ve been doing this work for a long time, and it’s inevitable that there will be good pieces and bad on the big issues of the day. I write because I think you should know your piece was troubling to a lot of seasoned observers of this issue. If you decide to follow up, please let me know, I’d be pleased to discuss the issue with you.

Sincerely,

Wayne Pacelle

President & CEO The Humane Society of the United States

www.humanesociety.org

Reviving Slaughter of Horses

Rules Changed as More Animals Are Cut Loose by Their Owners in Tough Times

U.S. NEWS| Updated May 3, 2012, 7:48 p.m. ET

By: DOUGLAS BELKIN and NATHAN KOPPEL

EMINENCE, Mo. – Jim Smith rumbled down a dusty road in his truck to check on the herd of wild horses he has been looking after near this tiny Ozarks town for more than two decades.

The herd, which got its start when horses were abandoned during the Great Depression, is growing again as tough times have pushed owners who can no longer afford to feed their horses try to give them a fighting chance in the wild.

Mr. Smith, who runs a trail-riding operation and captures many horses to limit the herd size and protect the newly abandoned “dumpouts” from harm, thinks there is a solution that makes many people uncomfortable: the slaughterhouse.

“The horse industry has gone to hell in a handbasket,” said Mr. Smith, a 67-year-old with a shotgun and a rifle in his pickup. “An old horse, a crippled horse, an unwanted horse, they all cost the same to feed, and nobody wants them, so they keep dumping them off here. Until there is a place to take them, it’s not going to get any better.”

To the relief of some – and the horror of others – that day may be approaching. Companies are planning to revive the horse-slaughter industry in several states, including Missouri, thanks to new rules authorizing federal funds to again be made available to inspect the facilities.

The Growing Herd

These horses, part of a wild herd in Eminence, Mo., were captured and corralled.

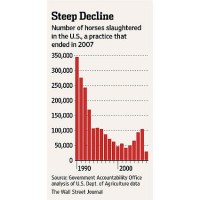

In 2006, Congress, bowing to animal-welfare groups, cut off funding for inspections, effectively shuttering the domestic industry. Without federal inspections, slaughterhouses can’t ship horse meat to Europe and Asia, where it is consumed by people. The last domestic horse slaughterhouse closed in 2007; as recently as 1990, more than 300,000 horses were slaughtered annually in the U.S.

Congress reversed course last year, authorizing funding for inspections after the Government Accountability Office concluded that the closing of domestic slaughterhouses had caused a decline in horse welfare, partly because it prompted more horses to be transported long distances to Canadian and Mexican slaughterhouses, without adequate rest, food or water.

A horse can typically bring several hundred dollars at slaughter. According to the GAO report last year, the demise of the domestic slaughter industry drove prices for all low-end horses down by 20%, while the tough economy drove prices down an additional 5%.

By 2009, owners who couldn’t afford the average annual cost of $2,500 to care for a horse also were having a hard time finding buyers. Reports of horses starved or abandoned surged, and rescue facilities across the country began to fill.

In Eminence, a community of 600 people 150 miles southwest of St. Louis, folks have been looking out for decades for the wild horses, which move along the Current River in Ozarks National Scenic Riverways, a large national park. After the park tried to have the herd removed in the mid-1990s, Congress stepped in and protected the herd’s status but capped its number at 50.

Mr. Smith and his pals created the Missouri Wild Horse League to protect the animals, which are good for tourism. In the past five years, the group has held the population to 50 by capturing, and then adopting out for free, 40 or so newly abandoned horses. Some horses are able to crack the herd’s stiff social hierarchy and win acceptance. Others failed to thrive and have been found dead.

Last Friday, Mr. Smith drove his truck slowly down a one-lane road in search of the herd. One of the region’s richest sources of revenue here is tourism, and trail riders come from across the country hoping to catch a glimpse of the wild horses. An hour away from his ranch, Mr. Smith stopped his truck. “There they are,” he said, pointing toward nine horses, heads down grazing, in a meadow framed by oaks and sycamore. A bit closer, he saw a young reddish colt. “That’s a dumpout,” he said. “We’ll have to come back and get him.”

Now, as abandoned horses vex communities across the country, companies are applying for permits to restart the slaughter industry. “This would be good for our economy,” said Rick De Los Santos, spokesman for Valley Meat Co., which wants to open a plant near Roswell, N.M., that would employ at least 50 people.

But the plant faces pushback. New Mexico Gov. Susana Martinez, a Republican, wrote a letter last month to Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack, urging the agency to deny the application, on animal-cruelty grounds.

Another company, Unified Equine LLC, based in Wyoming, hopes to build slaughterhouses in Missouri and Oklahoma by the end of this summer.

Animal-rights groups call horse slaughter inhumane; horses are sensitive, they say, prone to try to flee during the slaughter process. “Horses are often hit multiple times on their head before they are rendered unconscious,” said Nancy Perry, senior vice president of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

Critics of slaughter plants also maintain that unwanted horses can always find a home. “Most people would love to have a horse, and here are people using and discarding them as if they have no other purpose than to generate commerce,” said Susan Wagner, president of Equine Advocates, which operates a horse sanctuary in Chatham, N.Y.

In the Ozarks, patience for animal-rights advocates is limited. Mr. Smith says he has a hard time adopting out the horses he captures and can’t charge a fee to cover his costs. Meanwhile, car wrecks involving horses have become weekly occurrences, according to highway officials.

The newly abandoned horses, which are less adept at foraging, also tend to more aggressively invade backyards and private meadows.

“I don’t know of any horseman who doesn’t think we should reopen the slaughterhouse,” said Phil Moss, who lives in nearby Ellington and who helped build a corral to trap the newly abandoned horses on his property after they started grazing there. “We need to do something pretty quick.”

Be sure to write to Douglas Belkin at doug.belkin@wsj.com and Nathan Koppel at nathan.koppel@wsj.com and let them know you appreciate them bringing this important issue to the forefront and would like them to continue to write about these topics, however, please let them know the facts they left out of this article and the misrepresentations in their reporting.

Saving America’s Mustangs | 2683 Via De La Valle, G 313 | Del Mar | CA | 92014

Thought you would also enjoy this article on Forbes.com rebutting the WSJ article: “WSJ Serves Up Tainted Journalism On Horse Slaughter Plate”

http://onforb.es/JlOnKV

Published May 10, 2012 on Forbes.com